Popular has a slightly different connotation in today’s language, but it derives from the same root as “population” and “populous”: meaning “of the people”. What I try to do here and at Double X Science is write popular science, covering topics I hope are interesting for an audience with little to no scientific background. Many of my friends and colleagues are also in that business, and they take it seriously. Popularization isn’t vastly different from teaching: the goal isn’t to tell well-informed people what they already know or to impress them through jargon, but to reach out to intelligent people whose area of knowledge isn’t the same as the author’s (or teacher’s).

At the same time, hopefully popular science writing shouldn’t be boring to experts, either: I consider it a mark of a good physics writer if they hold my interest even if it’s a subject I know well. Even on familiar ground, it’s unlikely I know everything, so it’s possible to discover something new even on familiar ground. The best writers (and I definitely don’t count myself in that number!) are able to inspire such new discoveries, and you can tell who they are because their fellow experts read everything they write.

A Lonely Death to “Dumbing Down”

I was prompted to think these thoughts today because of a recent post by Adam Ruben, titled “The Unwritten Rules of Journalism“. In the post, Ruben mocks lazy practices by science journalists (sensationalism, use of cliches, etc.), and some of his points are fair, at least for some writers. However, he crosses a line and openly mocks popularization:

Don’t think of what you’re doing as “dumbing down” science. It is, but don’t think of it that way.

So, congratulations, everyone! You’re dumb. You don’t know everything someone else knows, so you’re stupid, and anything that person writes that reaches out to you is condescending. (Also implied: I’m dumb when I read something by Ed Yong or Sci Curious. That this remark cuts both ways seems to escape Ruben.)

Deborah Blum (journalist and author of The Poisoner’s Handbook) and Soren Wheeler (of Radiolab) both dismembered Ruben’s article, so I won’t rehash their arguments in detail, though inevitably our points do overlap. In fact, I’d say my blogger colleagues’ output is often a direct refutation of many of Ruben’s points: they dismantle sensationalist stories, provide real scientific details, and teach the reader something new…all the while highlighting science as a human endeavor, performed not by faceless automatons, but by real people with thoughts, feelings, and relationships.

I’m not interested in the “scientist vs. journalist” debate, partly because I’m a trained scientist who works as a journalist (in my role as writer for Ars Technica). I didn’t go to journalism school, so no doubt in someone’s view I’m not a real journalist. I certainly can’t seem to get the hang of the “inverted pyramid” style of story structure, nor yet of brevity, though thankfully my excellent editor doesn’t require perfection on those counts. In other words, I don’t care if the person I’m reading is a trained scientist, a trained journalist, both, or neither—the story they tell and the science they explain is far more important.

Everyone is an Outsider

It is possible to “dumb down” a topic—write it in such a way that the real information is lost. Some people (and many scientists are guilty of this kind of thinking, as my Double X colleague Jeanne Garbarino points out) deride all popularizations as “dumbing down”, since you can’t fill in all the details necessary for a complete understanding. If you want to fully understand the physics of the Higgs boson, you need a lot of physics (including basic quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, and classical electromagnetism, which all have prerequisites in the curriculum) and math (group theory, partial differential equations, linear algebra, and the kind of geometry you don’t learn in high school). I’m certainly no Higgs expert, but I hope I understand it well enough to provide a summary to help others comprehend why it’s a big deal.

Everyone is an outsider in a field that’s not their own. I’m incredibly ignorant of genetics and geology, and my knowledge of chemistry is fragmentary. Even within physics (and math), I know some areas much better than others. In fact, in some of these blog posts, I’m writing as much for myself as for you: I’m teaching myself about a topic, using you as an excuse. When I was in the classroom, I’d go out of my way to teach a new topic for that reason as well. There’s nothing like explaining something to another person, since teaching is a great way to expose your own ignorance—and a better opportunity for correcting that ignorance.

Real Errors Vs. Simplifications

One area I write about occasionally that makes me more nervous than any other is history. Physics and astronomy have long histories, and much of that received history is wrong, incomplete, or at least misleading. I really hate to get the facts wrong, but it’s almost inevitable that I will from time to time, since I’m not an historian and not all my sources are going to be correct. (I also know one of my historian colleagues will yell at me loudly if I do make these errors. He knows who he is.) So, in my history posts, I try to focus on the science and keep the history in the background, playing to my strengths.

I bring this up because I know I make a few persistent errors when I write about history: I refer to Galileo, Isaac Newton, and the like as physicists and scientists. The problem is those terms—and their related concepts—didn’t exist. Newton was known as a natural philosopher and mathematician, though he helped lay the foundation (a cliche! I fail!) for much of what we call “physics” today. (I also called Newton the “mack daddy of physics” last week at ThirstDC, which is definitely not an historically accurate term…not to mention that Newton himself considered his greatest life accomplishment to be dying a virgin.) However, I still call him a scientist and physicist, because these are terms my readers today understand, even if they aren’t accurate.

This is a simplification, and I argue a necessary one, as opposed to a real error. If I said Galileo invented the telescope, that would be real error, and you’d be right in picking on me, but if I say Galileo was a scientist, I’ll defend my terminology. It’s important both to understand people in their proper historical context, but also to bring them into ours, to recognize them as real people—even if it means calling them by a term that didn’t exist in their own era, such as “scientist” or “mack daddy”.

The Transit of Venus and the Beauty of Popular Science

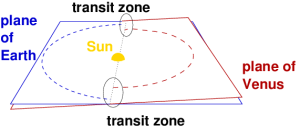

Today marks a truly rare event: something that happened only twice in our lifetime, and won’t happen again before we’re all dead. That event is the transit of Venus, when the planet eclipses the Sun in a small way. I wrote about this for Double X Science, so I won’t repeat what I’ve already said. However, if you want an excellent illustration of how popular science can take you deep into real scientific work, the Venus transit provides one.

By reading the various physics, astronomy, and general science blogs, you can learn about:

- the history of astronomy from Amy Shira Teitel;

- how to view the transit from Summer Ash or from Nicole the Noisy Astronomer;

- and how transits help astronomers look for planets orbiting other stars from Caleb Scharf.

In addition, if you go look at the transit, you’ll be participating in a rare experience, joining with huge numbers of other people from many countries, all looking up. That’s the beauty of popular science: not isolating or alienating people, but bringing them together to celebrate the joy and wonder of discovery.

7 responses to “Congratulations! You’re Dumb!”

[…] Congratulations! You’re Dumb! – Matthew Francis […]

[…] Congratulations! You re Dumb! by Matthew Francis […]

[…] Congratulations! You re Dumb! by Matthew Francis […]

[…] Congratulations! You re Dumb! by Matthew Francis […]

[…] Congratulations! You re Dumb! by Matthew Francis […]

[…] lot of people (including me) had a freewheeling discussion over the last two weeks about science communication and how it […]

[…] (For a lot more about Venus transits, please read my Double X Science post on the topic! I also mentioned it briefly in an earlier post about science communication.) […]